West Africa Ebola Outbreak Highlights Need for PREDICT Program

By Gorilla Doctors Staff on Friday, August 22nd, 2014 in Blog.by Jessica Burbridge

On August 8, the Ebola virus epidemic rapidly spreading through West African countries was formally declared an international public health emergency by the World Health Organization. WHO director Dr. Margaret Chan called it “the largest, most severe, most complex outbreak [of the Ebola virus] in the nearly four-decade history of the disease.”

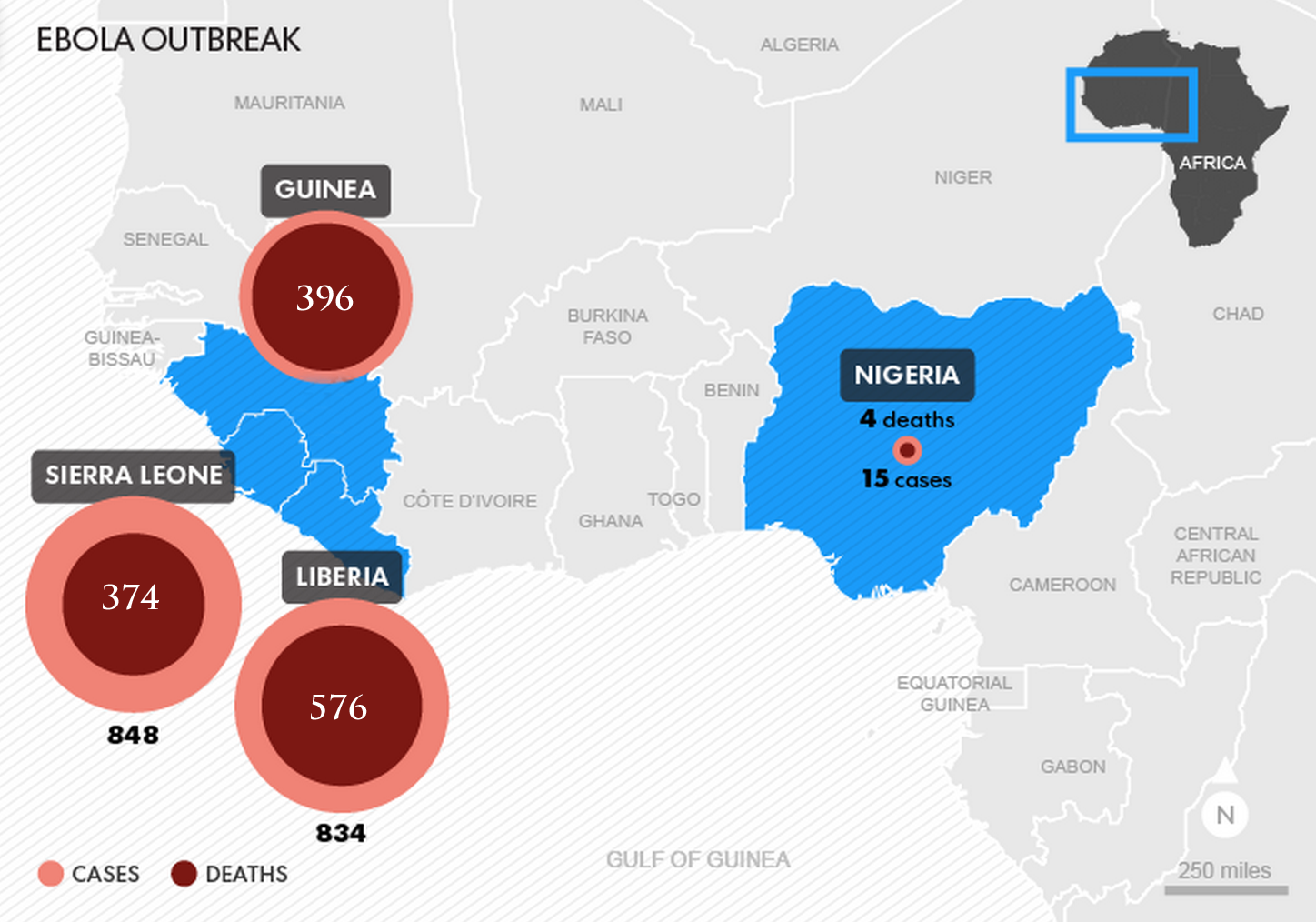

As of August 18th, this outbreak has claimed the lives of 1,350 people and infected 2,473 since March 2014. First appearing in Guinea, the virus gradually spread over into Liberia and Sierra Leone, and is now also in Nigeria (which does not share a border with Liberia, Sierra Leone or Guinea), with fifteen confirmed cases and four deaths. Liberia and Nigeria have declared a state of emergency and the governments of each country are undertaking serious measures to limit the spread of disease, such as enforced quarantine and curfews. Several commercial airlines have stopped service in the West African countries as well.

Ebola virus disease was first described in people in 1976 in two outbreaks in Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo. There have been more than twenty outbreaks in human populations in Central and West Africa over the last 38 years.

Ebola outbreak in West Africa in Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria.

Ebola outbreak in West Africa in Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria.

Infection with Ebola virus causes fever, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle pain and bleeding, with symptoms taking anywhere between 2 to 21 days to appear. The virus is spread by direct contact with bodily fluids such as blood, sweat, urine, saliva and diarrhea. While there is no cure, it is possible to survive the Ebola virus with supportive care. Some strains of the virus have a case fatality rate of up to 90%; the current outbreak if West Africa has a case fatality rate of a little over 50%.

Drugs to treat those infected with Ebola are in the early, experimental stages of testing and development, as are vaccines for prevention of infection. It could take months, if not years, for these experimental drugs to pass clinical trials and be officially approved for human use. That said, preliminary results are promising: Liberia’s Minister of Information, Lewis Brown, announced this week that three African doctors infected with the virus have shown “remarkable signs of improvement” with an experimental serum known as ZMapp. American aid workers Dr. Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol, who were both infected with Ebola virus in Liberia, also received the experimental drug and made a full recovery.

Dr. Kent Brantly, an American doctor infected with ebola in Liberia, and the first person to receive the experimental serum Zmapp.

Dr. Kent Brantly, an American doctor infected with ebola in Liberia, and the first person to receive the experimental serum Zmapp.

Does Ebola Pose a Threat to the Gorillas?

Ebola virus is also lethal for great apes: conservation experts report that Ebola virus outbreaks have decimated some populations of chimpanzees and western lowland gorillas. Ebola-Zaire, which is the strain causing the current West Africa outbreak, is suspected to have claimed the lives of over 5,000 western lowland gorillas in northern Republic of Congo’s Lossi Sanctuary between 2002 and 2004.

Though initial spillover of the virus likely came from a reservoir host, most Lossi Sanctuary gorillas appeared to have been infected by other gorillas (Bermejo et al., 2006). This is the same manner that the virus spreads through the human population. The challenge is that, while human Ebola outbreaks are controlled in part by isolating infected people, wild great apes cannot be isolated from one another, which means an outbreak is impossible to control.

Ebola, classified within the family of filoviruses, is a zoonotic infectious disease, which means it passes between animals and people. In fact, the first reported case of a known primate-to-human transmission of Ebola was in West Africa in June 1994 when a primatologist became infected after performing a necropsy on a chimpanzee found dead in the Taï National Forest. (Formenty et al., 1999). During this 2-year epidemic, 50% of the chimpanzee population died from the Ebola virus (Le Guenno et al., 1995). Three other Ebola virus outbreaks between 1995 and 1997 in northeastern Gabon were suspected to be linked to the hunting and killing of wild chimpanzees. In the second outbreak, 18 people involved in killing and butchering a deceased chimpanzee became infected with the virus, with 4 patients dying within 48 hours of infection (Georges et al., 1999).

According to the World Health Organization, human Ebola infection has been associated with the handling of infected chimpanzees, gorillas, fruit bats, monkeys, forest antelope and porcupines found ill or dead or in the forest. Wild great apes are not the reservoir, but simply susceptible hosts, just like humans. “When an ape is infected with the virus, the incubation period is short, so the chances of a human getting the virus from great apes without coming into direct physical contact with a sick or deceased ape is extremely small” said Gorilla Doctors Co-Director Dr. Mike Cranfield.

Although Ebola vaccines are still in experimental stages, some have shown promise in protecting laboratory monkeys from Ebola infection.

“Vaccinating wild great apes should really be considered as a last resort, after all other available measures to prevent an infectious disease from impacting the population have been put in place,” said Gorilla Doctors Co-Director Dr. Kirsten Gilardi. “That said, if the situation is dire and the consequence of not vaccinating is certain mass mortality, then the decision to vaccinate wild great ape populations at greatest risk should be on the table.”

How Are We Protecting our Gorilla Patients?

As a zoonotic disease, Ebola is directly linked to conservation: conducting thorough wildlife disease surveillance and minimizing human/wildlife conflict will be paramount in preventing a future outbreak.

The current outbreak underscores the critical importance of wildlife disease research, such as the work being done through the USAID-funded Emerging Pandemic Threats PREDICT project. Since 2009, Gorilla Doctors has been in charge of implementing the PREDICT project in Uganda and Rwanda, and our PREDICT veterinarians have worked in places where people and wildlife come into close contact to conduct surveillance of wildlife (such as primates, bats, and rodents) for viruses that may pose an emerging pandemic threat. Both PREDICT teams carefully monitor information on outbreaks of highly infectious diseases such as Ebola virus and Yellow Fever in human populations as well. Our PREDICT teams have traveled to outbreak sites to collect samples from domestic and wild animals in order to determine if the outbreak is related to contact that people may have had with wild animal populations.

In Africa, while the wildlife reservoir for Ebola virus is unknown, several species of fruit bat, particularly Hypsignathus monstrosus, Epomops franqueti and Myonycteris torquata, are considered possible natural hosts for Ebola, because molecular testing has detected Ebola virus positive animals, even though they do not exhibit signs of infection.

Gorilla Doctors PREDICT veterinarians collect samples from a fruit bat near Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda.

Gorilla Doctors PREDICT veterinarians collect samples from a fruit bat near Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda.

“If Ebola was reported in Rwanda, Uganda, or DRC, Gorillas Doctors would recommend shutting down tourism to prevent exposure of the gorillas to the deadly virus from people,” said Gorilla Doctors Co-Director Dr. Mike Cranfield. “The gorilla population would continue to be monitored for signs of illness and with appropriate permission from the governments, we would obtain the vaccines safely used in captive chimpanzees and have them shipped to the region. If there was a suspicious case of mortality we would collect samples to confirm Ebola and then ask permission from the host governments to vaccinate the population.”

A high percentage of mountain gorillas are habituated to human presence, making it theoretically possible to vaccinate the majority of the population via remote darting systems. In fact, in 1990 at the request of the Rwandan government, Gorilla Doctors vaccinated dozens of mountain gorillas with a human measles vaccine when measles was strongly suspected to be causing a lethal outbreak in the gorilla population.

“The present vaccine trials of the Ebola vaccine, which uses only portions of the virus and thus can’t cause the disease, has shown very promising results in monkeys and great apes” said Dr. Cranfield. “…although the studies have used small numbers of animals and long term effects have not been studied.”

Preventative Measures Implemented in Rwanda & Uganda

A 2000 outbreak of the virus in northern Uganda infected 425 people and claimed the lives of 224. The government quickly implemented a travel ban to and from northern Uganda, isolating the outbreak and successfully stopping the spread of the virus. Dr. Benard Ssebide, Gorilla Doctors Research Project Coordinator for PREDICT Uganda, sees the current spread of Ebola in West Africa as particularly problematic because “the local people do not understand what Ebola is and what causes it. They believe it is a curse from God — that it afflicts those not living in Godly ways. They chase away doctors or health officials from their villages. When they get sick, they hide.”

In contrast, according to Dr. Benard, “…people are quick to report themselves to a hospital or local clinic when they become ill in Uganda. They will promptly be isolated and given supportive care, drastically reducing the chances for the infection to spread.”

Intensive screening has been implemented in both Uganda and Rwanda’s airports, and already several individuals with fever and other symptoms who have landed in Kigali or Kampala have been quarantined, though none have tested positive for the virus.

Gorilla Doctors Head Rwanda Veterinarian, Dr. Jean Felix Kinani, recently participated in a meeting organized by the Ministry of Health to discuss plans to protect the country from an Ebola outbreak. Educational posters and 35,000 flyers have since been distributed to hospitals, health centers and doctor’s offices throughout the country. Isolation facilities have been set up at various points throughout Rwanda and personal protection equipment has been distributed to hospitals and health clinics while hundreds of health care workers are receiving “refresher training” on the treatment of the Ebola virus.

As the West African countries continue to fight the spread of Ebola, governments around the world are preparing to protect their countries from potential infection. Gorilla Doctors will continue to work closely with the Rwandan, Ugandan, and Congolese health ministries to protect both the local human population and the critically endangered eastern gorillas from this deadly virus.

For more about the Gorilla Doctors PREDICT work, click here.

To listen to Dr. Kirsten Gilardi’s recent interview on “Ebola and Zoonotic Disease Surveillance” on KDRT, click here.

Donate

Donate