Rwanda: A Resilient Country, Risen from the Ashes

By Gorilla Doctors Staff on Monday, April 7th, 2014 in Blog.by Dr. Jean Felix Kinani

Twenty years after the genocide, Rwandans have shown the world that our wounds can heal even though we will never forget the past. Through us, the world sees that a country can recover from extreme violence spurned by division and hate. Rwanda suffered the systematic extermination of more than a million people in just 100 days in 1994. Even now, burials are still taking place for skeletons recovered from latrines and mass graves.

During the time of the genocide, my family and I lived in my birthplace of Lubumbashi, in the South of Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). I remember seeing the events on television, witnessing the indescribable cruelties. I remember my father telling me that this was the worst period of his life. He received frequent letters announcing the deaths of his family members that lived in Kinihira village, in the southern province of Rwanda. Back then, the area was called Mubasinga. During the genocide, we lost 75% of my father’s family. My father took care of the Tutsis that survived in Kinihira village, providing education and support. He moved back to Kigali in 1996 to join in the rebuilding of Rwanda; I stayed behind in Lubumbashi to finish my veterinary medicine studies. In 1998, the Tutsi extermination ideology was running rampant once again, only this time, in DRC, and Kabila’s army was being attacked regularly by the RCD (Rally for Congolese Democracy) rebel movement, which was allegedly receiving support from Rwanda.

During this war, all Congolese Tutsis were identified and were either arrested or killed by DRC soldiers, FDRL, Zimbabwean and Angolese soldiers who came to DRC to protect the government. I was arrested in 1998 and spent 11 months in Bakita, a 5-bedroom house used as a Tutsi concentration camp containing almost a thousand people.

Five months after I was arrested, we were visited by the Red Cross and were given the opportunity to leave the jail for 30 minutes to get some sun, take our first baths, and have our conditions assessed. Every day we ate a piece of ubugali (corn meal) and a spoonful of beans at 3 pm. Each morning, we were asked to stand up for identification control and each one of us had to stand for 2 minutes before the jailers. Apparently it was an exercise requested by authorities to make our ordeal more difficult. After 8 months, we received additional food and were evacuated by force to Rwanda. Once I was free, I left for Senegal where I would spend 3 years finishing my degree in veterinary medicine.

There were many Rwandans who hated one another in Senegal, a climate maintained by former Rwandan government officers who had been exiled to French-speaking African countries. The entire time we were there, we were reminded of how our people had suffered and continued to suffer in the Congo. I remember during the 8th commemoration of the Tusti genocide, I read a Boris Diop piece with these powerful words: “les innocents ne sont pas morts, ils se reposent”: “innocent people don’t die, but they rest”. My father’s family members were not killed with guns, but with machetes and spears in the village where they lived. They suffered a lot. ‘Les innocents ne sont pas morts, ils se reposent’ gives me relief that they are at peace now.

Moving Toward a Brighter Future

I joined my father and four of my sisters in Rwanda in 2003 after completing my studies. For the first time, I was able to see and feel the change and growth that had taken place in the country – especially in the tourism sector. My first job and my great passion is to work with the Gorilla Doctors where I serve as the Head Field Veterinarian for Rwanda and coordinate the health care of the mountain gorillas in Volcanoes National Park.

Dr. Jean Felix Kinani, Head Field Veterinarian in Rwanda.

Dr. Jean Felix Kinani, Head Field Veterinarian in Rwanda.

I’m proud to have worked as a Gorilla Doctor for eleven years now. We have a great team of veterinarians and through our medical interventions and other extreme conservation practices, the mountain gorilla population has grown by 26%. In fact, they are the only endangered species of wild great ape that are increasing in number. The mountain gorilla success story is a product of intricate collaboration between the Rwandan government and many partner organizations working in the region.

Dr. Jean Felix (center in grey shirt) with staff from the Fossey Fund and the Rwanda Development Board.

Dr. Jean Felix (center in grey shirt) with staff from the Fossey Fund and the Rwanda Development Board.

We feel that we are apart of this Rwanda success story, through our role of providing medical care to the mountain gorillas and our One Health initiative to support the health of the human and wildlife populations. Through the revenue sharing program implemented in Rwanda, citizens living around protected areas receive 5% of the Rwanda tourism profits, which is helping to reduce poverty in the country, as well as improve healthcare and hygiene, and reduce food insecurity.

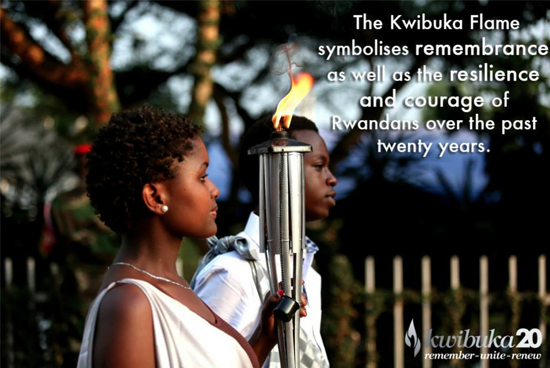

On January 7 this year, Rwanda launched the Kwibuka 20, which, in Kinyarwanda, means “remember”. Kwibuka 20 is a series of events taking place in Rwanda and around the world, leading up to the annual genocide commemoration, beginning on April 7. “Twenty years later we, Rwanda, ask the world to unite to remember the lives that were lost. We ask the world to come together to support the survivors of the genocide, and to ensure that such an atrocity can never happen again – in Rwanda or elsewhere. Kwibuka 20 is a time to learn about Rwanda’s story of reconciliation and nation building.” (www.kwibuka.rw)

Kwibuka 20: Remember, Unite, Renew.

Kwibuka 20: Remember, Unite, Renew.

Rwanda has become one of the fastest growing economies in the world. Despite the trauma the country experienced in 1994, Rwanda is now ranked as the “easiest place to do business in the region” following the 2012 Doing Business report.

H.E. President Paul Kagame said “we cannot turn the clock back nor can we undo the harm caused, but we have the power to determine the future and to ensure that what happened never happens again.” Over these last 20 years, Rwanda has risen from the ashes of a horrific genocide to become a country it’s citizens are proud to call home. I believe that I speak for my fellow Rwandan brothers and sisters when I say that “I am proud to be a Rwandan”.

Donate

Donate